Unveilings Along the Liquid Highway

Lesley A. Wolff, PhD

“We are all bodies of water…As watery, we experience ourselves less as isolated entities, and more as oceanic eddies.” *1

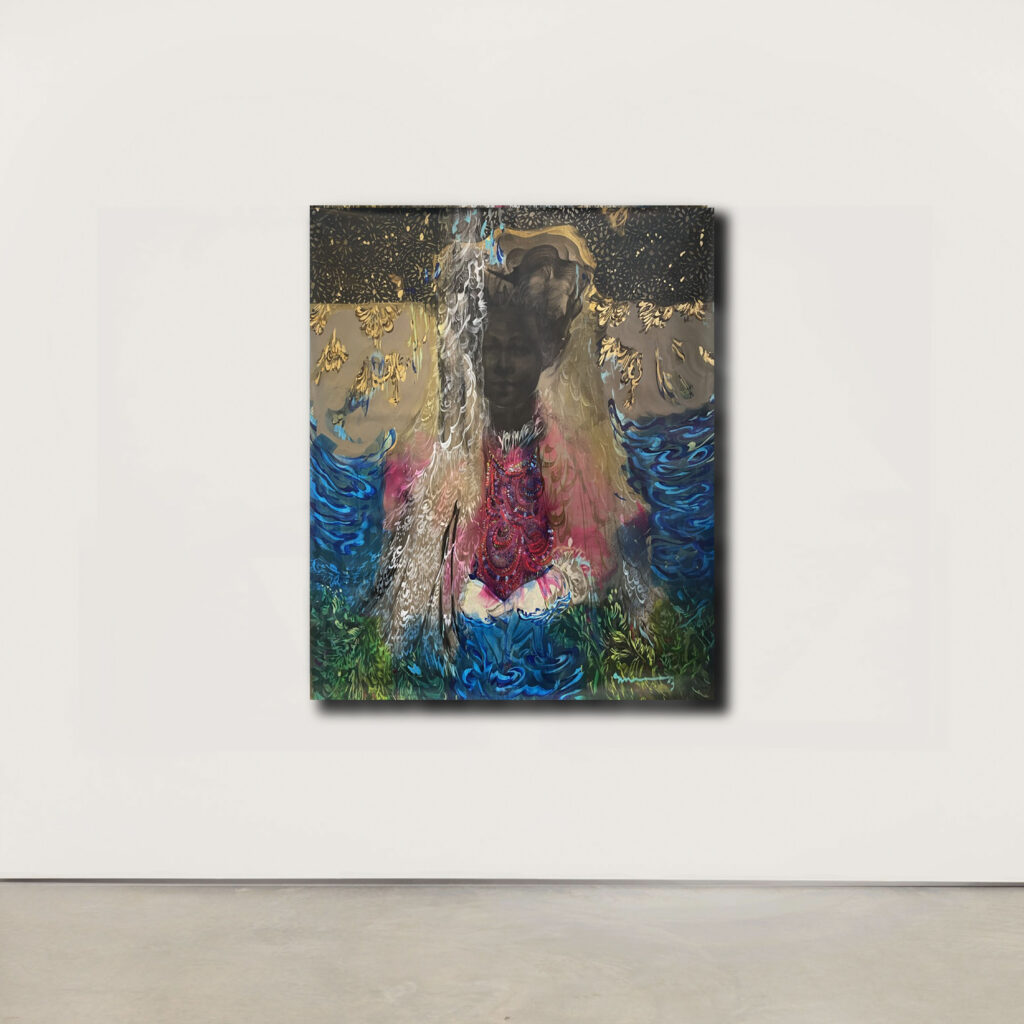

If, in the words of cultural theorist Astrida Neimanis, we move through this world as “oceanic eddies,” then Scherezade García is our visionary, offering insight into this epoch of rising tides through color, line, and form. For decades, the artist, who emigrated to the island of Manahatta/Manhattan from the island of Kiskeya/La Hispaniola, has been conjuring ways of imagining life with and through the seas. In Under the Lace: Stories of Floating Cathedrals, Resilience and Encounters, García’s follow-up to her 2021 solo Praxis exhibition Stories of Wonder: When the Sea is My Land, we meet a series of ethereal figures suspended within an aquatic expanse. Elegant and unyielding, these women float amid the blue seas, engulfed in tropical flora and ornate textiles whose opacities at once veil and reveal the figures beneath. In A Splendid Soil I, the figure at center gently flirts with our gaze, an island unto herself, surrounded by the eddies of waves, flora, and lace. Like a saint animated in a baroque altarpiece, the figure’s presence contrasts the ebbs and flows of the gestural waters, while the resplendent hues and swirling brushstrokes remind us that she is unmoored from land, awash in movement. As with all of García’s works in this series, the composition depicts a seemingly infinite expanse of foliage, feathers, textiles, jewels, and water; it is also a metaphor for the gravitas of diasporic embodiment in our watery world. García’s figures may seem to be adrift at sea, but their stoic presence roots them among the tides. In this way, García gives visual presence to lifeways that transcend conventional depictions of home, belonging, and memory.

In recent years, artists, scholars, and writers have become increasingly captivated by the seas, their cumulative work giving way to what has become known as the “liquid turn” or the “blue humanities.” For these makers and thinkers, the liquid turn embraces processes, species, places, and ways of being transcendent of the landlocked heteropatriarchal and Eurocentric conventions that have long determined not just the marketplace of ideas, but also the marketplace of images. García’s exploration of what she has come to call the “liquid highway,” a metaphor for and archetype of water’s visuality—layered, fluid, transformative—stands at the forefront of this movement and continues to evolve in ways that position her at the avant-garde of creative investigations into the memories and futures floating in our seas. In 2006, on liquidity’s resonance with notions of resilience, liberty, and migration, García proclaimed,

The frontiers of the places I love are liquid. The liquid has been an inspiration to me; it amazes me. I understand it as a frontier and as a road to salvation as well. These waters move, taking away and bringing me back, no doubt full of treasures and dreams. *2

García’s career-long commitment to liquid highways, frontiers, and salvation began with the series Tales of Freedom (Leonora Vega Gallery, NY, 1996-98) and has taken myriad material forms over the years, from pink floatation sculptures in Endless Love (1998), to literal lifesavers used by refugees in the interventionist work Sabana de la Mar/Action of Salvation (Sabana de la Mar, 2003), to the “tropical barroquism” of the painted series Súper Trópico (Lyle O. Reitzel Gallery, 2015) *3. In 2015, Garcia debuted In Transit/Liquid Highway (Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University; expanded in 2019 at the Losaida Center, New York). This

large-scale installation, composed of cresting waves, marks a significant inflection point in García’s work, in which the water and its mutability came to embody the endless psychic and physical ebbs and flows of the diasporic experience in her own Latinx community and beyond. Yet, if the sea has long been a significant touchstone in García’s work, it represents shifting ground that refuses singular form or meaning.

The phrase “liquid highway” evokes notions of modern ease of transit, of constant motion from one destination to another. The liquid highway also invites a deeper critique, one that implicates the violent routes of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, whose brutal voyages formally ceased in the 1860s, only to be replaced by submarine communications cables that trace global capital through the very same routes now submerged below the surface. Thus, for García, the liquid highway conveys meanings both personal and global, moving spatially and temporally. As aquatic repositories of earthen elements, such as dust, ash, and sand (themselves material compressions of myriad times and places), the seas quietly “carry portents of other times, both anticipatory and remembered,” migrating across the very same routes as ancestors trafficked for enslaved labor, displaced by war or famine, or who otherwise sought personal refuge.*4 The persistence of the seas also foreshadows the millions whose displacement is yet to come and attests to migrations happening this very moment. For García, “everything is connected to the idea of how tangible this moving water is.” In other words, the seas, paradoxically, invite one to think about “ancestry and land.”*5 As a self-professed “Dominicanyork” artist who proudly claims pan-Caribbean and pan-American/hemispheric heritage (and all of the slippages therein), García knows what it means to traverse the seas and to hold the conceptual fluidities wrought by those voyages within her memory and work. García’s knowledge thus transforms her canvases into more than a metaphor; rather, her work unveils the anatomy of our watery world and the beings born in and of its wake.

As worlds end, collide, and begin anew on an increasingly liquid planet, García considers what it means to stay afloat. In A Splendid Soil I, the figure sits in a pink flotation ring, both a reference to survival tools in the open waters and to García’s body of work since the late 1990s, in which the pink lifejacket recurs as a motif of survival and heroism in the tropics. To stay afloat is a complex notion, one that suggests persistence and resilience. To stay afloat also suggests the idea of being at sea, to be unmoored or displaced, in a liminal wake between the steadfast terrain of home and an elsewhere. Along the margins of the composition, a floral frame contains this oceanic abyss, and yet at top right the foliage begins to dissolve, the frame coming undone at the seams—a beautiful, ruinous, structural unraveling. This world ending invites futures both promising and menacing for the floating figure, who relies not on that framework to buoy her, but rather on the steadfast, if isolating, flotation device that carries her and her alone through this watery world.

While García has hinged much of her work on the liquid highway, she continues to challenge precisely how we define and perceive liquidity, especially within the contexts of imperialism, colonialism, and diasporic migration. In this way, García is always forging new frontiers in diasporic visuality and memory work. In Under the Lace, García asks us to consider how fluidity might be understood through other forms and objects. All materialities come from and return to water—this concept underscores García’s work and gives physicality and visual presence to what the artist calls the “politics of inclusion,” an ethos that informs the multi-ethnic, multi-racial, and multi-temporal references and figures that abound within her compositions.

García reconsiders liquidity in A Splendid Soil II, the complementary composition to A Splendid Soil I. Unlike the first work in the series, which depicts a figure clearly afloat at sea, this work obscures its liquidity. The figure at center sits among flowers in what appears to be a lush and splendid garden under a glittering night sky. Yet García tells us that this is no ordinary portrait, as the seemingly land-bound figure dons a voluminous and luminescent pink flotation device around her bust. Does the lifesaver betray this migrant’s journey that led her to this point? Or perhaps anticipate a journey to come? Or might the lifesaver be more metonymic in nature, conjuring strategies of resilience and survival in a world ill-equipped to face the literal and metaphorical rising seas? In her lifesaver, this figure is impervious to forces that seek to pull her under—she is adept and adaptable. Looking closely, one sees that the lush garden surrounding the figure rests atop a blue surface, a watery bed that supports the buoyant flowers and figure alike. The water becomes fertile soil for the emergence of this stunning scene—the “land,” as it were, has sprung up around the figure. She is the origin point, the place-maker. She need not be situated on land to cultivate her garden; rather, the garden sprouts from her abundant waters.

As the figure rises and falls with the waves, her dress delicately skims the surface, drawing our eye to the fibers, patterns, and dyes that this woman literally carries on her back. García’s artistic trajectory has led her to produce increasingly baroque and maximalist compositions in recent years, with myriad textures rendered as layers beneath, atop, and around the figures at center—a reference to migratory materialities and to García’s early training in fashion design at the famed Altos de Chavón School of Design in Santo Domingo and Parsons School of Design in New York. This exhibition’s namesake composition, Under the Lace I [Bajo el Bordado I], shows how the artist transports the notion of liquidity into new material frontiers. The dark-skinned figure gazes out at the viewer, her face calm, if perhaps melancholic, against the patterns and gestural brushwork that envelop her. She seems to effortlessly rest above the water’s surface, her lifesaver but a hidden suggestion beneath a delicate, cascading mantilla, that falls from the top of the composition into the water, where the suggestion of lace merges with the blues of the sea and the greens of the foliage.

Indeed, in this work, the lace is but the suggestion of lace; the cross stitching gives way to calligraphic gestures evocative of Islamic script, emphasizing the multitudes of influence that have shaped the Americas and diasporic communities emergent from colonial encounters. Like water, the lace gestures toward the same ambiguities and slippages that weave through García’s entire oeuvre. Lace as we know it emerged in sixteenth-century Europe, a pivotal time of imperial expansion that included the development of the Spanish colonial city of Santo Domingo, the site of García’s birth, which she has called “the first European city in the Américas.” It was during this era, as systems of capital, enslavement, and globalization began to fester and grow, that the delicate, networked threading of lace became fashionable, particularly across the Spanish empire.

For García, the materiality of lace—a fabric that plays with presence and absence, positive and negative space, and one that is easily transportable, across lands, across oceans, across time—embodies lifetimes of rituals, stories, and journeys: “I see cloth as carriers of memories, the clothing for baptism, the attire for a carnival. The prints on the fabric reveal many journeys and relationships with different soils…The lace beautifies but also camouflages.”*6 In her recent work, García uniquely highlights the lace mantilla as a touchstone motif, conjuring its historical associations with female modesty and forbidden beauty; it is a suggestive garment intended to highlight as much as it conceals. According to García, this heirloom garment also embodies “African-al-Andalus memory” and the pluralities that comprise syncretic African and Middle Eastern influences in Spain, which in turn made their way to the Americas via transatlantic voyages. The title of this exhibition, Under the Lace, is thus something of a provocation (what lies under the lace?); and García unveils her response as the resiliency of women. Behind the mantilla, under the lace, these figures carry their beliefs, stories, and histories as they traverse worlds.

If the baroque stirrings and opulence of García’s work offers a seductive entry point into her compositions, it is the steadfast gaze of the figures that becomes the locus around which all other elements orbit. In this way, viewing a work by García is a peripatetic act, the gaze moving across myriad forms and colors. In this journey, the face of the figure in each of García’s compositions becomes a landing site, a place of respite, an anchoring force. According to García, the visages of her figures comprise an amalgam of the women in her family. The figure is neither portrait, nor ghostly visitation, nor an archive re-traced, but rather a manifestation of memory work in the present. Thus, even though the figure feels imminently grounded, she embodies a syncretic and fluid identity, rejecting fixation in or determination by one time or place. García underscores this notion in her triptych Harvest of the Sea, which features three individual women with attire from Africa, Europe, and the Americas, each on their own seafaring journeys. Although they possess individual agency as unique figures, they unite (knowingly or unknowingly) via resplendent golden sashes that, like sails, seem to carry them in harmony. It seems no coincidence that these women converge on the seas, the originary site where their heritages, stories, and experiences became forever entangled.

1 Astrida Neimanis, “Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water,” in Undutiful Daughters: Mobilizing Future Concepts, Bodies and Subjectivities in Feminist Thought and Practice, eds. Henriette Gunkel, Chrysanthi Nigianni and Fanny Söderbåck (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 85.

2 Scherezade García, “From Amor Eternal to Sabana de la Mar,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Platform for Criticism 19 (Feb. 2006): p. 100.

3 See Camila Maroja, “Meandering Pathways: Tropical Barroquism in the Work of Scherezade García,” in Scherezade García: From This Side of the Atlantic, ed. Olga U. Herrera, pp. 16-24 (Washington, DC: Art Museum of the Americas, 2020).

4 Ayesha Hameed, “Sea Changes and Other Futurisms,” in Visual Culture as Time Travel by Henriette Gunkel and Ayesha Hameed (Sternberg Press, 2021), p. 47.

5 Studio visit with the artist, June 29, 2023.

6 Correspondence with the artist, July 12, 2023.