The Harmony of the Spheres

By Denise Carvalho

“For the very end of myths is to immobilize the world: they must suggest and mimic a universal order which has fixated once for all the hierarchy of possessions.” 1

“In a word, I do not yet see a synthesis between ideology and poetry (by poetry I understand, in a very general way, the search for the inalienable meaning of things).” 2

The visual world of Maria Berrio is imagined through a constellation of narratives and feelings, sometimes contradictory, other times repetitive and reflexive. Like an extended polyphony, which is lived in multi-levels and in multiple worlds, it invites us to think identity and culture a bit like the indeterminacy of the aesthetic event, as a consciousness gravitating toward other consciousnesses, inter-merging and reconstituting their own events. We can enter through her eyes as they traverse within the image, and connect to all the marks of her trail, and all the colors of her emotion. In this universe of possibilities, her main characters are young women that differ in their attire and expression, whose roles are to protect and nurture our ecosystem, a desire for the grandness of the heart. It is this myriad of suspended and intertwined shapes and meanings that identify a mythological idea of time, in which finite things and events are confined to an eternal recurrence. In it, different feelings and actions can happen all at once, as illustrated by the juxtaposed motifs. The repetitive signs or situations can be linked to mimetic histories, showing that even in the era of technological machines, our perceptions of the world appear belated, as they are driven by a blind search for a lost intimacy with our habitat. 3

The Harmony of the Spheres comprises paintings/collages that explore a desired balance between ancient and contemporary sensibilities. As in Pythagoras’ theory in which orbital bodies in motion produce a harmonious sound in their attunement, Berrio’s non-linear narratives tune in through an integrative disposition of elements in search of beauty and resonance. Her principle of attunement begins when determinate, measurable, and intelligible organizations of mediums and materials complement the fantastic, poetic, and ethereal vocabulary of her visual domain. The grid, traditionally as an organizer of three-dimensional pictorial space, is here dissolved into degrees of approximation or influxes between distinct and colorful patterns. Papers from all over the world become archaeological traces to be excavated and rediscovered. The Japanese paper assembled in rituals and offerings, or the gift-wraps—the skin of commodities—converge ebulliently beyond their original memories and social functions as unnamed cultural signifiers. Other substances also encode the pleasure of their application, a return to a primal tactile experience before language, rekindling the medium as an extension of the body. The body, in its turn, is devoid of intentions, but vigilant to identify unknown wonders. Finally, her collages revolve into paintings, as residues from the collated paper mutate into the canvas as paint.

The extension between collage and drawing is also significant, as lines are determined by a confluence of margins, expanding the possibilities of continuity between one form and another, one story and another. Her never-ending line is a segment of many finite points, but also a curve or a circle of endless radius, indicating her work’s circular time, as myths may seem. If we consider the art practice as an alternate plane in which basic topological figures take place beyond the frame, Berrio’s drawings begin to be boundless curves or segmented signs, created by patterns that are extended to life itself, as she cuts with the pencil and draws with the scissors. Her interwoven traces grow to be a connection of energies embedded in a single flow of energy, as the case of a composition of sounds or similar traces of an image, constantly mutating, decoding and encoding through new assemblages of resemblances and meanings.

At first, our eyes intercept the shifting and colorful fields demarcated by foregrounded repetitions and excesses, as in byzantine mosaics. Then, we surrender to the delicate simplicity of her pencil drawings on semi-raw surfaces, depicting the serene faces of the women and girls that populate her canvases. Do they arise as individual characters from her imaginary world, or different nuances of the same female figure? The reflective innocence of these feminine faces remind us of Pablo Picasso’s Rose Period, while the gestural components where contour and motif collide allude to Gustav Klimt’s paintings. Another reference is Rousseau’s naturalism, conveyed through the symbolic narratives and story telling of her collages. Different from the surrealist influences of earlier artists such as Frida Kahlo and Remedios Varo, where autobiography derives from an identity split or from the repressed unconscious accessible through dreams, Berrio’s work intends no divisions or binary contradictions. It emphasizes a new awareness, in which humans live in tune with and close proximity to animals and plants, where place and resources are allocated to all species, cultures and identities.

Although biocentrism, ecocentrism, and environmental ethics can be implied in her works, her interest is to highlight expanded potentialities of consciousness, or a new cosmology shared by all beings co-existing in harmony. In our real world, this would be impossible without strong international laws forbidding the unethical treatment of animals, preserving laws that protect endangered species, and banning deforestations and biodegradable erosions by corporations. But more so, it would be impossible to act upon these laws without reawakening our kinship with the land.

Berrio’s reference to wild life is inspired by South American folklore and recreated through her autobiographical accounts and memories. Born Again, 2015 is a powerful allusion to Madremonte or Marimonda—Mother Nature in Colombian mythology—a protector of forests and animals, but implacable to humans who attempt to destroy its domains. In the painting, a beautiful woman carries a live jaguar on her shoulders, representing the strength of womanhood. Jaguar woman wears a veil of flowers—seen also among Yanomami women’s flowery headdresses—which here blend with her garment. Her face is adorned with a fringe of beads hanging over her cheeks, maybe a reference to facial scarification or jewelry used by women from various societies and periods to enhance their beauty or to protect against evil spirits. The pattern of the live jaguar’s fur is integrated into her body as a vest, honoring the woman’s animal ancestors. The jaguar sitting on the woman’s shoulders reminds us of the legend of Heracles or Hercules, who carries a lion’s fur on his back, seen in ancient Greek and Roman sculpture and black figure painting. Strength is symbolized by the jaguar, protector of the underworld, and prevails in the physiological and spiritual metamorphoses that take place during motherhood, shared by animals and humans alike. Its resilience in the spiritual body contrasts the fragility of life itself, depicted by the image of a small bird held by jaguar woman. The message is simple: not just human life is at stake, but the life of the whole planet.

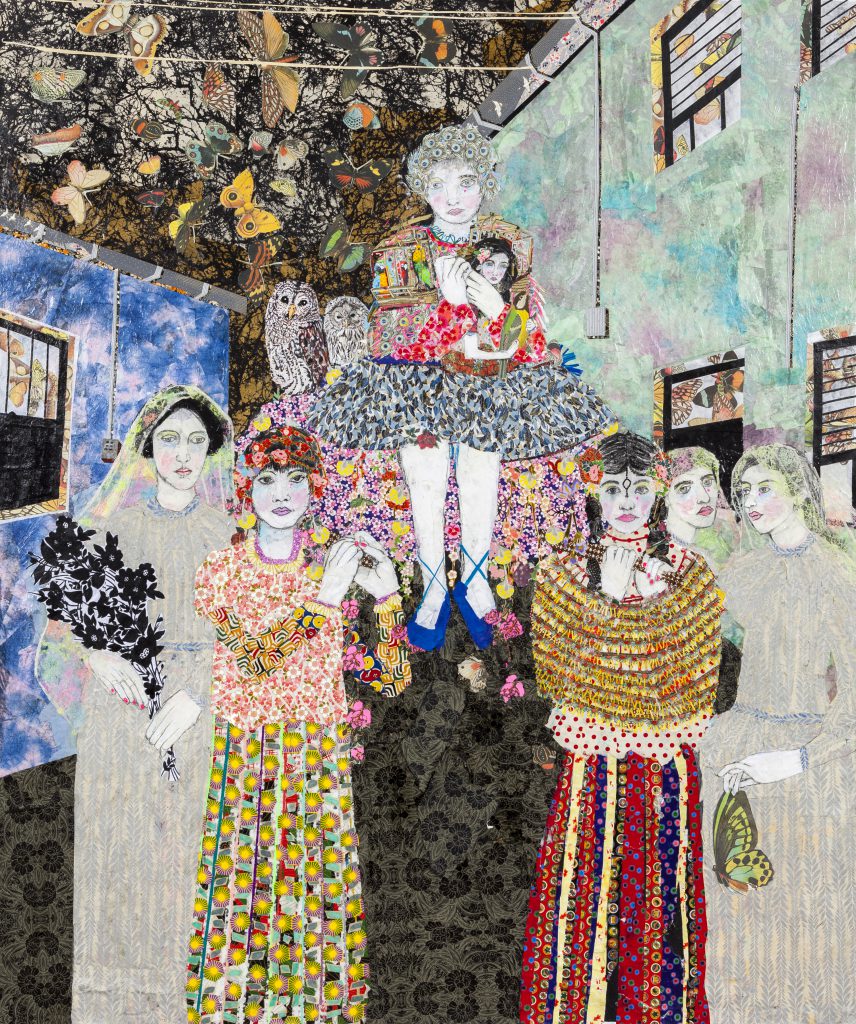

Another source of inspiration in Berrio’s work is magical realism, delineated through forces of nature or supernatural beings, often making allusions to historical or biographical situations. Her depiction of butterflies began after she read Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. In the novel, Meme’s love for the mechanic, Mauricio Babilonia, is manifested through hundreds of yellow butterflies fluttering around him.4 Butterflies constitute both a symbol of vigilance and desire in Berrio’s large paintings. The Procession (2015) echoes the artist’s earlier idealism as she migrated from her native Bogotá to New York, leaving behind a familiar paradise for a more precarious, unpredictable, and powerful life in the Promised Land. In the painting, two women with flowers on their heads hold a canopy as they parade across a narrow street. Butterflies emerge inside the windows of buildings, and in multitude, they fill the night sky, as their colorful wings appear threatening. Beauty suddenly becomes oppressive, overwhelming, and hopes of a better life ahead appear undetermined. Over the canopy, a young girl with her hair covered in peacock feathers sits facing the viewer with an innocent glance. Behind her, two owls symbolizing wisdom seem to observe and protect. On the girl’s lap is a miniaturized woman holding a large butterfly. The girl and the miniaturized woman create an embrace inside another embrace. Three other women with veiled faces appear in the painting; one holds a bouquet of black flowers as awareness of her mortality. The female gazes convey all their feelings into one, an amalgam of their silence, aspiration, alertness, longing, solitude, self-reliance, and awe. Distinct flowery and geometric marks create the fabric of their clothes, blending with the more dimmed ornaments of the buildings’ walls. The architectonics of difference is distilled into the great sublime.

The Lovers (2015) calls forth the nostalgia and longing from a bygone synchronicity between humans and nature. In The Kiss of the Butterfly (2015) a woman with a contemplative expression embraces a giant butterfly in a kiss. A kiss between a person and a butterfly is symbolic of a magical experience in the loving connection between two completely different beings. The argument here is not that we should project on animals or insects our own fancy or needs of affection, but that we can find a deeper sense of accord with the natural world inside ourselves, as we expand our capacity to identify with the stranger (whether people or species). The Lovers 2 (2015) displays a similar theme of a young woman embraced by a flamingo around her neck. The woman’s expression of solitude, camouflaged by a transparent veil with repetitive pink geometric shapes, is mirrored in the flamingo’s eyes, creating a sense of wholeness or gestalt in which the two figures merge into one. Love is the realization that the animal kingdom is before us, our ancestors. Honoring their dignified existences is finding a primordial unity with our natural environment. The annihilation and degradation of animals and forests as if their value only exists for us, not in themselves, is a deranged rite. As we reduce the natural world and ourselves to a thing among things, we grow unaccountable to our own history and to our future.

In Knitting the Wind (2015), female twins lie on a bed next to birds and below clotheslines, as musical moods or visual poems hang from one building to another. The two figures inform the ethnic and cultural duality experienced by the artist, displaced between opposite sides of the equator. The bed also references a burial ground, a mnemonic of one’s mortality. A hint to the ancient myth of Atropos, one of the Three Fates who decides the fate of one’s death, is suggested here. Yet, the stretched arms and legs of one of the twins, as a bridge between two buildings, assert that the journey continues. As the women blend with the repetitive geometric designs of their clothes, of the windows and sky, they dissipate into a kaleidoscope of distinct perceptions of depth and distance, reality and memory. The idea of knitting also evokes the traces of the journey, tying and untying, marking and erasing boundaries. Not ancient as weaving, knitting is exemplified by pulling threads through loops, resulting in fragile knitted fragments that hardly stand the test of time. Like the fleeting fragments of memory, knitting tools can be easily transportable from place to place, as the twins follow the steps of their ancestors in the transitory search for home. These patterns convey life’s rhythms (musical, mathematical, aesthetic), as they are approximated by their likenesses.

As dualities and differences vanish within infinity, chaos appears as if never tangled and always at play. This is what Maria Berrio’s paintings generate. In nature, nothing is repeated but transformed. The repetitive geometric and organic patterns are all elements of nature, deceived by the simulacra of their own meanings. 6 As a systemic order, they disseminate their own particularities into an abstract oneness. As we envision a world of multiplicities, because everything transforms, we further erase distinctive nuances, receding further back into a process of visual contemplation. Still, the glance of the artist remains undisturbed, unveiling what needs to be unveiled, as she is guided by an idiom of transformation.

1 Roland Barthes, Mythologies, p. 155. New York: Hill and Wang, 1998.

2 Ibid, pp. 158-159.

3 Georges Bataille, The Accursed Share, New York: Zone Books, 1991.

4 Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude, US: Harper and Row, 1970.

6 Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 290, New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Dr. Denise Carvalho is a scholar, curator, and art critic. She holds a dual Ph.D. in cultural studies and M.A. in art history from the University of California, Davis, a Masters in anthropology from Hunter College, and a B.F.A. from the School of Visual Arts. In 2013 and 2014, Dr. Carvalho was the Andrew Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow for the exhibition, Via Brasil, at the Wexner Center for the Arts, and a visiting graduate professor of art history at Ohio State University.

Dr. Carvalho’s curatorial experience encompasses “Love at the Edge” (2015) at the Arsenal Gallery Power Station in Bialystok, Poland; “Beyond Limits” (2014) as part of the Post-Global Biennale at the San Diego Art Institute; “The Unknown” (2012), curating the Americas at the 3rd Mediations Biennale in Poland (2012), “Minimal Differences” at White Box in NY (2010), and “Preemptive Resistances” at the Westport Arts Center in Connecticut (2009), among others. Her upcoming exhibition “AMOR” (2016) will be held at Oi Futuro Flamengo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

As an art critic, Dr. Carvalho has published in art magazines and journals, including Art in America, Sculpture magazine, Art Nexus, NKA Journal of African Contemporary Art, Afterimage, and The International Journal of Art and Society. She has also written essays for numerous artists’ catalogues. As a professor she has taught at various universities in the United States, including San Francisco State University, Humboldt State, New Jersey City University, School of Visual Arts, and was an assistant professor at the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts. She is currently a visiting professor in contemporary art at Indiana University in Bloomington.