Praxis is pleased to present In a Time of Drought, the solo exhibition by Maria Berrio (b. 1982, Bogota, Colombia). A reception to celebrate the opening will be held at our new location on 501 West 20th Street, NY, NY 10011, on Thursday, September 7th, 2017 from 6 to 8 pm.

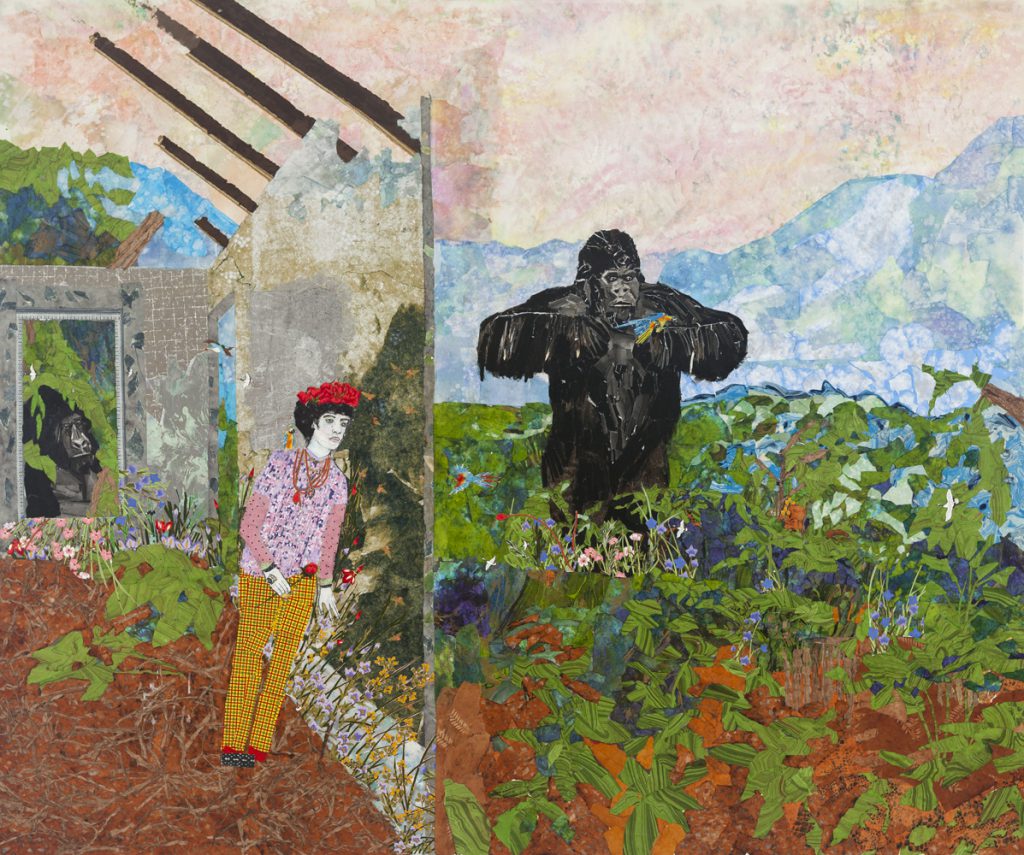

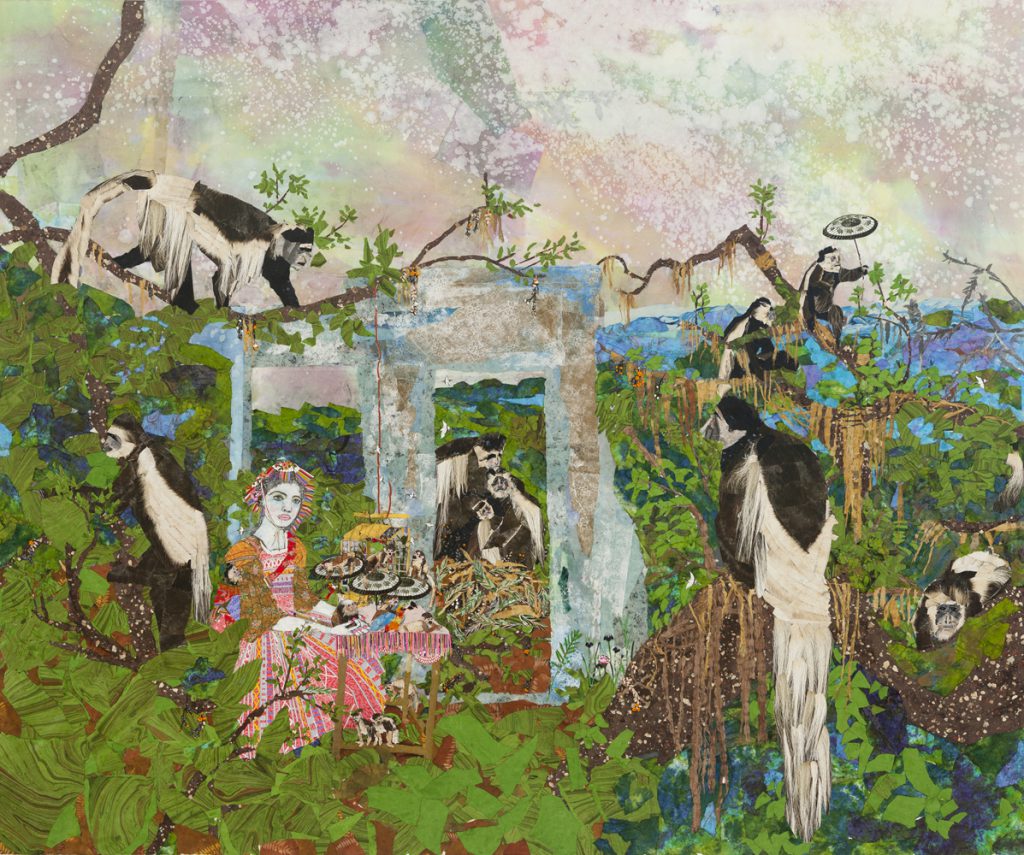

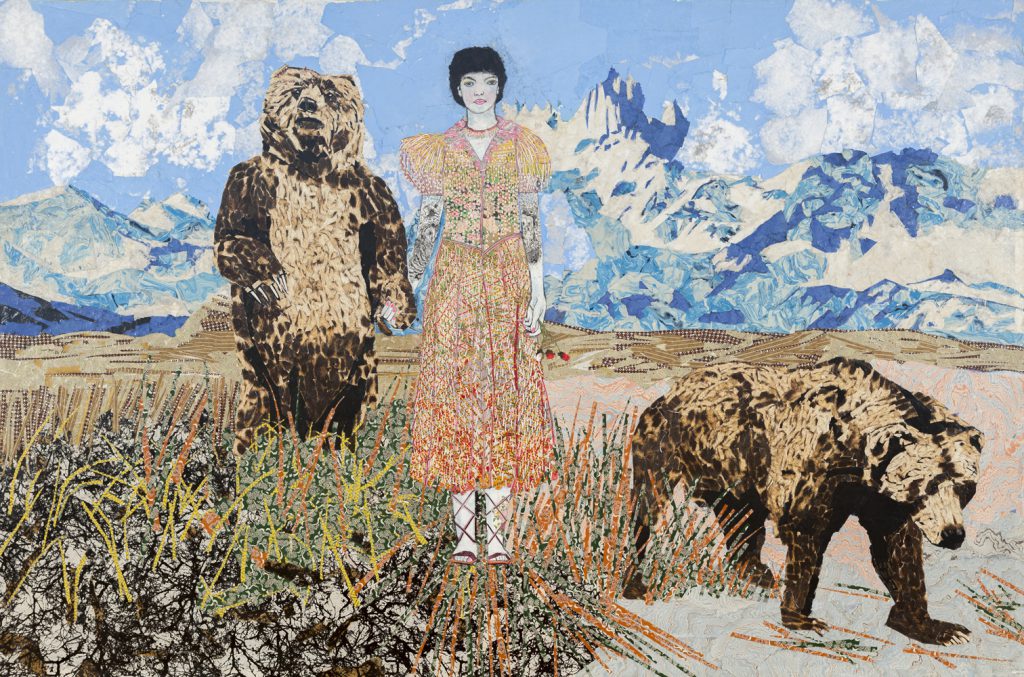

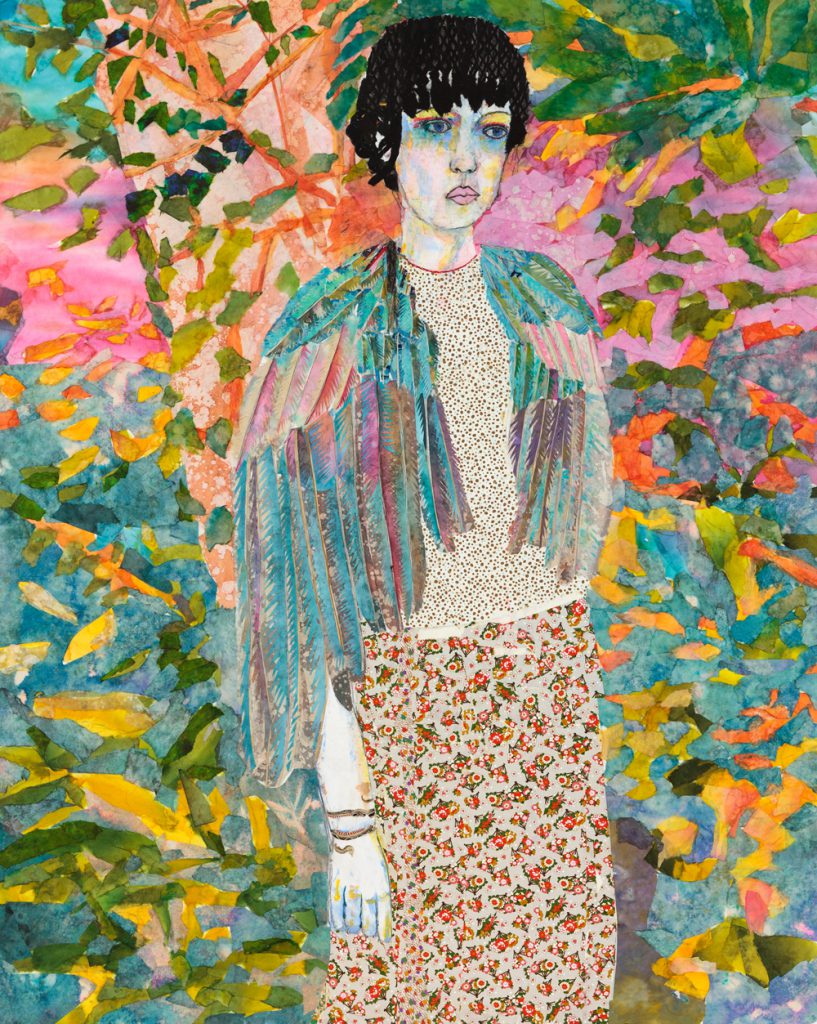

In A Time of Drought Maria Berrio’s latest series began with using some of the dioramas found at New York City’s Natural History Museum as a starting point. From there, she allows her own world to seep into those iconic scenes, altering them in such a way that they are transformed into something utterly her own. Many of Berrio’s hallmark symbols and themes are still present. Depictions of powerful, perhaps archetypical, women stare back at the observer, projecting an unflinching strength of will and of spirit. Still lifes of the animal world have become ruminations on humankind’s place within it, on how each influence one another. Just as museum dioramas serve as romanticized educational content to emulate a sense of “really being there“ for the viewer, Berrio’s pieces employ magical realism to comment on how humankind’s evolution has decontextualized itself as a fellow living animal, completely detached from the natural order of the world. It is left up to the viewer to determine what is alive or a taxidermied and dressed figure. Berrio also seems to be commenting on how we are turning our own surroundings into a diorama: we trap our actual reality into a safely curated space, reduce the majesty of a sunset to a social media post without ever really engaging with what is there. Experience has been filtered and supplanted by a virtual reality. Yet the dioramas are only a springboard for themes and ideas it seems Berrio wants to address, and she refuses to confine her works within the narrow constraints of a glass-walled box. Take the piece from which this series takes its’ title, In a Time of Drought. Two mountain goats look down upon two women, one of the women supine on rocks while another holds two young mountain goats, a kid dangling by its legs from each of her hands. Its beauty, its lavish colors and rich details, is counterbalanced by something vaguely darker. The apparent innocence of the young women depicted in the work cannot belie the fact that the idea of a sacrifice comes to mind—but who is being sacrificed, and to whom? Is it a feminist nod to the story of Abraham and Isaac, perhaps one seen through the eyes of the ram? Or has the girl safely returned the kids to their parents, restoring nature to its rightful place—-a gesture of peace, or of contrition, on behalf of the human world? The overarching theme one finds in Berrio’s works is one of an uncomfortable ambiguity between our species and nature. This is seen in the painting In a Time of Drought, but is found throughout the entire show, perhaps best exemplified by East of the Moon, West of the Sun. Depicting a woman holding hands with a bear, its title comes from a Norwegian fairy tale about a peasant girl whose father marries her off to a bear in return for riches. In this work, the woman stares back at the viewer undaunted, a look projecting strength and bravery. Yet not only the bear, but the panorama of mountains, reveal that she is enmeshed in an environment where nature is likewise a powerful force. It is unclear if this is an ideal symbiosis or a romantic tragedy, a harmonious relationship or an abusive one. Perhaps her and the bear stare out defiantly together from the diorama box we have placed them in. Or perhaps the defiant look is directed to her circumstances within her world, a battle of wills, a powerful being rendered vulnerable in the face of greater force, but refusing to submit regardless. One senses there is a great deal going on behind that tranquil surface. The tranquility of Berrio’s works seems to be one that follows in the wake of violence, or is but the proverbial calm before the storm. It is perhaps most apparent in The Waltz. In it, a gorilla hulks on one side of a ruined wall while a young figure hides on the other side. The power dynamics bubbling beneath the surface of East of the Sun, West of the Moon have spilled over. Here is a universe truly red in tooth and claw, where the fickle trappings of humanity are overpowered by sinewy vines to the stuccato of thumped chests, beating out songs of deindustrialization. Our civilizations, rationalizations, moralities and beliefs have collapsed into a flimsy ruin. Yet the apocalypse of one species may simply be the rejuvenation of others. An idyllic landscape of soft mountains, flowers, and verdant foliage encroach over humankind’s gray footprint. It is an invasion of purity, terminally pristine. The Demiurge plays with similar imagery, but brings it to a different conclusion. In Gnosticism, the Demiurge is a creator god who himself was created, but is unaware of this fact. In his isolation he forms the material world, trapping aspects of the divine in materiality, ignorant of the transcendent, higher forms of reality. The Demiurge is a testament to the mystery of the creative drive itself. It depicts a woman seated at a table on which there are miniscule caged monkeys, while she is amidst a landscape teeming with plants and large colobus monkeys. The tiny simians perched atop her table seem but a shoddy replica of the boisterous life all around her, but they are a noble, if imperfect, attempt to encapsulate life’s grandeur. The infinite splendour and mystery of our universe cannot be captured in our creations, but there is splendour and mystery in our attempts to do just that. Creation was ascribed not to a creator god but to angels by earlier gnostic sects. The Nightingales 1-3 bring to mind angels on account of they being depictions of women with bird wings. Their wings may suggest the celestial, but their looks are those of deeply grounded beings. They are a secular seraphim at best, for the wings are either clipped short, devolving into a mere shawl, or they have only one wing. Berrio once mentioned in an interview that one of the reasons she paints animals making themselves at home in incongruous human environments and vice versa is it’s a way of exploring the experience of immigrant identity. Each character is made exotic because of her placement in a different environment, each is part but not-part. The Nightingales are a further meditation on the immigrant experience. The immigrant and the refugee is often exoticized and made into something somehow different from human, a part-creature. But these paintings seem to speak more of the aspirations of the immigrant, of the idealization and romanticising of distant lands, only to discover that the muck and mire of reality follows us no matter where we travel to. Perhaps the clipped wings speak of failed migrations, of thwarted attempts to reach promised lands or lofty goals. Regardless, the steely determination of these women is as apparent as their elegance. The Nightingales are not cowed by circumstance, nor are their dreams to be deferred. A woman’s reach should exceed her grasp, or what’s a Heaven for?

Tyler Burlingame New York, August 2017